How Kerberos Works

Summary

General idea

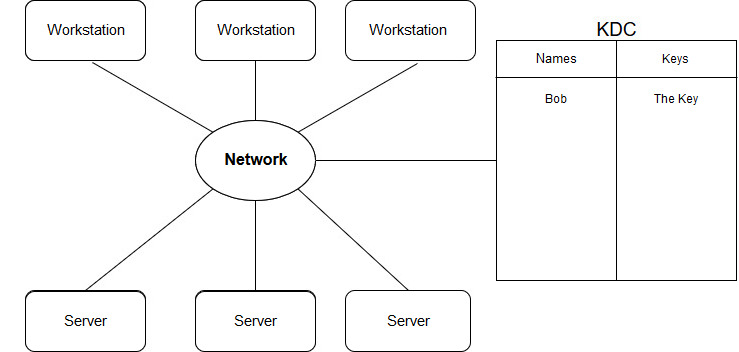

Kerberos was created to communicate with multiple user machines and multiple servers without needing to trust the network through which they communicate. The system is very successful and is the basis of Microsoft’s Active Directory. The general scheme is that we have one kerberos server that can issue Tickets and with their help all authentication of all network objects is performed and these tickets replace passwords in Kerberos system. This is cool because with a stolen tickets hacker especially can not do anything, but with a password can a lot of things and therefore it is much safer.

The most important things in this system are the keys that represent an analogue of the password in Kerberos, that is, having stolen his hacker has the opportunity to pretend to be the user or server whose key he stole. This key is a password hash and in the ideal model it (the key) is not known by anyone except the key holder and the KDC (Key Distribution Center). The latter saves all keys with the names of their owners in their own table and understands which key belongs to whom.

KDC services

KDC has 3 services: kpasswd, kerberos and TGS. Now let’s talk about the last two. In fact, they perform similar functions with some differences, they both issue tickets for services, but this separation is necessary for that the user does not enter his password every time he logs in and wants to ‘talk’ with the server’s services, because it is unsafe and annoying to the user. The kerberos protocol is needed in order to receive a ticket for the TGS service, which will issue more tickets for the services with which you want to interact. There are also 2 protocols here for more security, the kerberos service requires a user key in order to give a ticket for services, unlike TGS. Which is not too safe because in this case the key will be needed all the time and it can be stolen from the memory of the working machine . Therefore, after receiving the ticket for the TGS service, which will give us more tickets, since it does not require the user’s key to issue tickets, the key itself can be deleted after the ticket for the TGS service has been received.

It is also necessary to be careful with the re-use of kerberos names, the fact is that the name is only a row in the table and the new ‘Bob’ can have rights like the old ‘Bob’ and have access to old Bob’s files, therefore you need to be careful.

Ticket structure

So, the very first ticket for the future use of the TGS service is a common client and server ticket (Tc,s) - its structure:

Tc,s(client_name,server_name,ip_addr,timestamp,lifetime,client's_key,server's_key)Ks

Where Ks - is the key of the server with which the ticket is encrypted.

In this case, this is a request for a ticket for the TGS service and it is the server in this design.

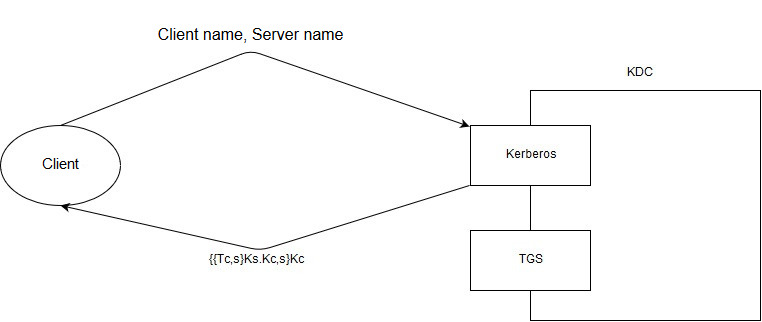

When a client wants to talk to the TGS, he lets kerberos know about it. The client gives only his name and the name of the service, in return receives a ticket encrypted with the client’s key for communication between the user and the service. The kerberos service response contains the public key for the client / service that will be used by both parties, and is encrypted with the service key that the user wants to contact, the general ticket for the client / service. Here is the structure:

((Tc,s)Ks; Kc,s)Kc

Where Tc,s - is Ticket shared between Client and Server; Kc,s - is Key shared between Client and Server; Ks - server’s key; Kc - client’s key.

Ticket Security advantage

The ticket (Tc,s) is encrypted with the server key so that the only thing that can be done by the person who receives the ticket (and this can be done by anyone before version 5) will give the ticket to the server with which you want to talk. In version 5, kerberos began to accept such requests only with the hash of the timestamp and client key H{timestamp, Kc} due to the possibility of an offline brute force ticket that was sent as a response. Also, in the 5th version, shared encryption keys were no longer used for the sake of a separate user and service, ie instead of one shared key, 2 separate keys began to be contained in the ticket.

TGS ticket for the TGS service with which you can get tickets from the TGS service, temporary, and the hacker will be able to work on behalf of the user only while the ticket is ‘alive’ and after some time it will no longer be valid, unlike the user key that only changes when changing the user’s password, which is not often.

Usually, this model is used to access the TGS service so that it can give you more tickets later. And, as I have already mentioned, the cool thing about this is to remove the client key from the memory after a user took a ticket for the TGS service when the machine was initialized, after the ticket to the TGS, we only need the key when we need to create a new ticket for the TGS. And if a hacker steals this ticket, then he can work on behalf of the user only while the ticket is ‘alive’ and after some time it will no longer be valid, unlike the user’s key which changes only when the user password is changed, which is not often. But the user will keep in his memory the shared key of the client and the TGS (Kc,s). The question arises, what is better than leaving Kc? One way to do this is for a hacker to fail to use it outside the connection for which this shared key was created.

Also for this, he needs these data from the kerberos (Tc,s)Ks response to communicate with the service, in this case with the TGS. If someone just takes a computer and takes it, all he gets is a ticket for the TGS, which is less evil than the password, as it gives access only for a while.

Work with TGS service

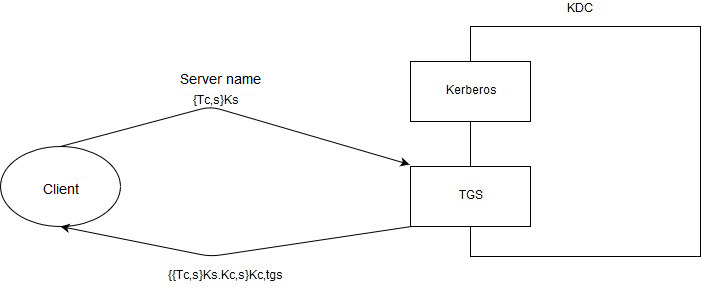

Now that we have a ticket to communicate with the TGS, we can ask him for tickets. We communicate with him in the following way: we (the user) send him: The name of the server with which we want to talk and the ticket (Tk,c)Ks that we received from kerberos. All this data is answered by the TGS in almost the same way that kerberos responded at the very beginning, namely:

((Tk,c)Ks; Kc,s)Kc,tgs

The only difference here is that now the entire response is encrypted with a shared key between the client and the TGS, since we no longer use the client key. Once again, back to the fact that in version 5, when establishing a connection, 2 keys are used, one for messages from the client to the server, the other from the server to the client. This approach protects against reuse attacks (replay) in which some server response can be used as a client request, while the key is common to them.

Security nuances

Now imagine a situation: we, as a client, want to access the server via ssh with the client name ‘Bob’, and we are not in the kerberos system, then we send our password directly to the server. And what does the server do? He goes to the KDC server and asks for a ticket for the user ‘Bob’ and the KDC sends to the server ticket encrypted with Bob’s password. The vulnerability is that we can play the role of the KDC and send this response for the ssh machine that reaches it earlier than the response from a real kerberos server. In other words, we can log in with any existing username, send any password to ssh, send a response supposedly from the KDC which will be encrypted with the password that we sent to ssh and the ssh server will allow us to log in. The protection against this is as follows: the ssh server, before requesting a ticket for us, asks the TGS ticket to talk to the same ssh server, in other words with itself. And if the ssh server can correctly decode the respons, then it knows that the KDC is a legitimate server, because it knows its key.

kpasswd

What happens if we want to change our password? In this case, the kpasswd service will help us. It accepts only the ticket that the user receives from the kerberos service to use the kpasswd service and changes the user’s password. Tickets from the kerberos service have one bit which indicates that this ticket is from kerberos and only such tickets are accepted by kpasswd, since only the kerberos service requires a client key that replaces the password in the general kerberos system. Because otherwise, a hacker can use tickets from the TGS that he could steal and which do not directly require the user’s key.

There is also the problem that a hacker can save change password packets that the user sent to kpasswd and that are encrypted with the client key. All this he did for a long period of time. Thus, if one day in some way the hacker finds out the old password of a user who does not particularly value them, it is old and he changed it for a long time ago. Then the hacker will be able to get the old user key and decrypt the password change request that once the user sent to the kpasswd service long time ago, and get the new password. In the 5th version of kerberos, the kpasswd protocol also uses the diffi-hellman algorithm, which adds an additional secret value for communication between the client and the server.

Conclusion

Here are the general principles of Kerberos, in fact, everything is not so difficult and in the overall picture is very safe, but such things as replay attacks or fake KDC responses remind that the devil is in a details.